Going Through Old Notebooks Part 5: Americans in Paris

Dear Reader,

Here is something I’ve reworked from some pieces of writing written in late 2020. I’m still not sure this counts as a completed essay, but here it is.

During the late summer of that first year of the pandemic, as I was trying to write my book, I enacted a distinctly American ritual. There were no tourists in Paris at the time, really no tourists at all; shopkeepers and taxi drivers and other French people I encountered would sometimes exclaim, with a certain kind of longing nostalgia:

“An American! But there are no Americans in Paris right now!”

That wasn’t strictly true, but I knew what they meant. The expat community was nothing compared to the usual sightseeing hordes.

The cafés were still open then, at least for a while, and I realized that the least crowded ones would likely be the most famous—you know, the tourist spots, those places where the outdoor tables were usually thronged with people, and lines of visitors snaked out the door. Young women in red berets and lots of makeup would pose for Instagram photos on the terraces, while South Asian men carrying large bouquets of flowers would walk up and down among the tables, selling roses to the couples. Not now, though—not anymore. For the moment, all of those people were gone.

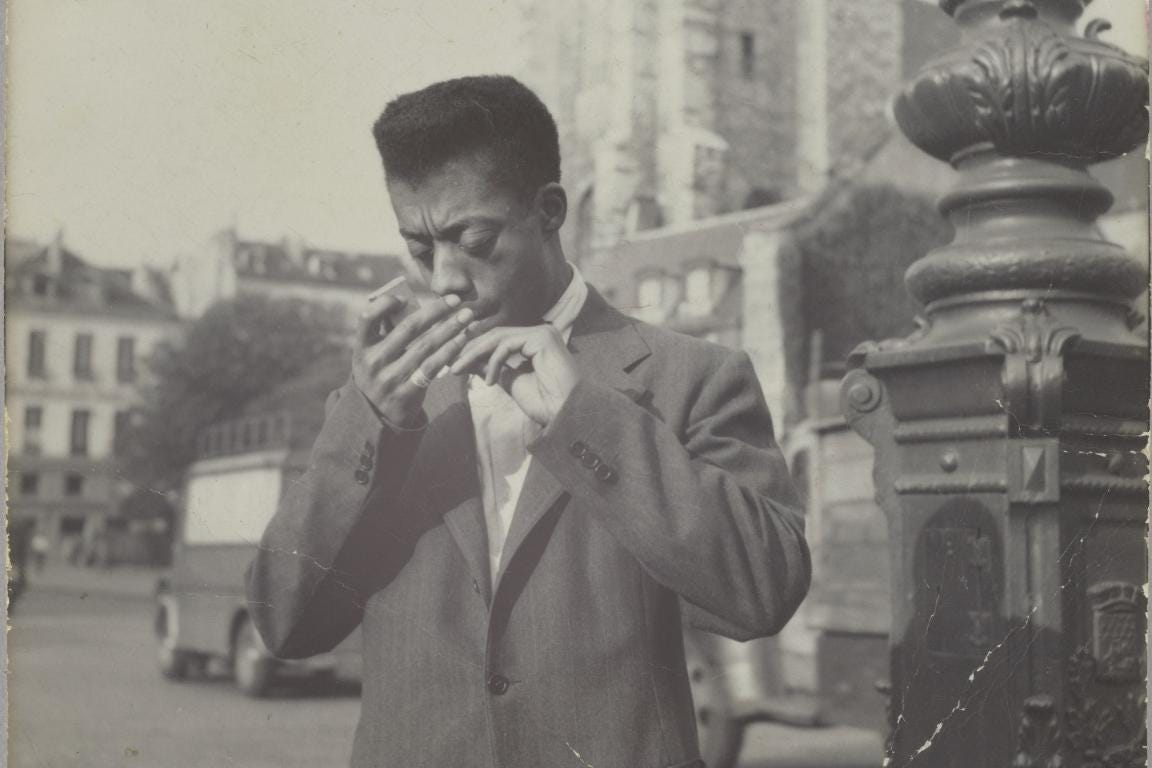

I figured that the safest places, the ones most likely to be deserted, would be the famous haunts of dead Americans—the preferred spots of writers like Baldwin and Hemingway—and I was right. This was how I ended up spending nearly every afternoon at the Café de Flore.

I would arrive after lunch, between two and four in the afternoon, when almost no one was inside. There might be a smattering of people on the terrace, but inside and upstairs, where Baldwin had sat with his portable typewriter, writing “Go Tell It on the Mountain,” almost all of the tables were empty, even through the dinner hour.

In the absence of tourists, the old writers’ cafés had been given back to the writers. There were usually only a few of them there when I arrived, mostly old men. One man, aged maybe seventy-five or eighty, would write his pages out on long individual sheets of paper, double sided, with a fountain pen. They looked like the sort of letters one might find in an archive, but I suspected that they were a novel. He would hang his wooden-handled umbrella from the Art Deco railing at the top of his banquette, take out his sheaf of papers, and begin.

Another man, who had the air of someone used to being thought of as important, was working on a screenplay. For several days he sat upstairs in Baldwin’s spot, alone, where I would see him when I went up to use the ladies room. Then he came down after a few solitary days of this, and sat with the rest of us.

Another older man was working from a stack of handwritten notes, which were color-coded with highlighter. He would type quickly on a small laptop, checking his notes often. I peered over at them once, one night as I passed his table, and saw that they were separated into sections: Chapitre 1, Chapitre 2, and so forth. On his screen was a game of solitaire.

These were the regulars.

Once, a handsome young Asian man in a black cashmere sweater and crisp white collar came and made handwritten notes on a printed manuscript. Another time, a fellow American woman came in with her laptop and took a phone call right in front of everyone, without stepping outside. We all stared at her. The café played no music. It was like she had stood on the table and started shouting. She didn’t stay long.

Every day, before opening my own wounded manuscript, I would order a hot chocolate with a separate cup of thick whipped cream, and then reread for the millionth time the first chapter of Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast. I know, this probably sounds sort of cheesy, but it’s where the ritual part came in. It acted as a sort of tether. Maybe an incantation. The rain, and the wind, and the “good café on the Place Saint-Michel,” and the timelessness of it all. It grounded me. The white wine, and the oysters, and the work, and the leering; the plans he made, with Hadley, to get away from the city and sleep in a country auberge in the snow, with the windows open at night; to be warm and safe in bed together, with each other, and with their books.

I had recently been gifted a beautiful volume of James Baldwin’s collected essays. Edited by Toni Morrison, it was fat with pages so thin, it was almost like a Bible.

I often thought of Baldwin in my early years in Paris, perhaps because he so vividly encapsulates the vision of an American abroad—the best of what such an experience can offer. It makes me think of how we either make space within a culture for the sensitive souls among us, or we don’t.

I think it helps to get away from America sometimes, if one wants to understand it; to understand its particular hopes and terrible cruelties, its dreams and sorrows, by letting them fall away from you for a time. The prejudices one faces in America are not gone in France—far from it. Any destination will have its own cruelties, its own terrors, but they are different here. The differences, the variety, the nuance—in them, there is something to be learned.

I have often thought that I feel less misogyny in France, but more sexism. I am expected to adhere more closely to certain feminine rules here, and greater feminized assumptions are made of me—or so it sometimes seems. But I do not feel hated in France, the way I sometimes do in the States, just for existing and no longer being twenty-two. As a woman who no longer passes as an ingenue, I feel there is still a place for me here; that I am still seen as a person—with desires, with an inner life, with potential; that I am still seen at all; this concept of a “prime of life” exists for me here too, and not just for my male peers.

None of this is why I came to France, but since I have been here, I have noticed it. The conflict over sex and gender has manifested differently here.

I often think of Baldwin, arriving on the Left Bank with virtually nothing, just after the war, and how almost immediately he fell gravely ill. He lay in his grim hotel room and might have died, if the Corsican woman who owned the hotel had not decided to nurse him; to climb the stairs each day and make sure that he had food, that he was still alive; to wave his rent for the three months that it took for him to recover.

I doubt that anything like that could happen now.

Any other conflicts I encounter as “the other” in France are national or class-based, not racial. I’m usually assumed to be either British or—and this surprises me—Italian. Apparently, I have a slight Italian accent in French, to the point that actual real Italians have sometimes exclaimed to me, after a brief exchange in French, and with real joy:

“An Italian! Where in Italy are you from?!”

Then I have to disappoint them. Sometimes they don’t even believe me at first, and I have to prove it by trying to speak Italian, which I cannot.

“But then why do you have an Italian accent in French?” they ask, confused, as though I have pulled a confidence trick.

“I don’t know,” I say. “I’m sorry.”

I once read an article on the Paris of James Baldwin. It was about where he went when he lived here, and where he might go, and live, and work, if he lived here now. Not in Saint-Germain-de-Pres, and not at the Café de Flore, the author had decided. In the end, the author said, Baldwin would likely not have come to Paris at all, that Paris was no longer necessary. It wasn’t needed the way it was to him then, when he said he had needed it to survive.

“My reflexes were tormented by the plight of other people,” Baldwin wrote. “Reading had taken me away for long periods at a time, yet I still had to deal with the streets and the authorities and the cold. […] I knew what was going to happen to me. My luck was running out. I was going to go to jail, I was going to kill somebody or be killed…”

This article about Baldwin, and about how someone like him no longer needed to come to a place like Paris, to escape the experience of being Black in America, was written at the start of 2014. Obama was still president. Almost twelve years later, it certainly feels possible that a person might need to leave America to survive—literally, or even just creatively.

Sometimes during that late summer of that first year of the pandemic, sitting in the famous café where Baldwin and Hemingway and others had wrote, I would look up from my laptop and find that all the others had gone home. It was 8pm, and people should be ordering dinner, but I suppose they had all gone home for dinner. I liked to sit near the large flower arrangements, which at that time of year included great big crabapple branches and sunflowers. The smell of orchards. I suppose they were keeping up appearances.

I wondered if the waiters missed the tourists, or were glad to be rid of them, since they weren’t paid in tips. When I would finally pack up to leave, one of the younger waiters always twinkled at me over his mask with his eyes and said, “see you again madame, very soon.”

I would stay in the café doing my work until ten, and then walk back through the deserted Latin Quarter, the empty late-night brasseries emerging from the dark streets, glowing red and gold, eerily immaculate, bright and floating in the night like ghost ships. I’d follow the arteries of the city, the streets and bridges, over the river, and up towards my own neighborhood.

Have you ever thought about putting together a sort of literary patchwork quilt based on your Parisian observations? It wouldn’t need to follow any kind of conventional format. It could just be a collection of your random vignettes - no narrative, no plot, just a stroll through the city. You tell it so well!

Mmm. Such a pleasure to see you back in print. Your baguette, beret, cliché-free vision of Paris is a joy to read. Keep trawling through your archives!