Introducing: The Essay Series

A rough guide to the different kinds of essays you may find yourself wanting to write.

Essays are a wild thing. There is something untamed about them. No matter how rational, how well-researched, how cool and removed an essay may appear, do not be fooled. It has been pulled from the dark estuary of the human mind. The writer has fished it out from that place of not knowing but of wanting to know, dripping wet, trailing reeds and brackish water. Its permutations are seemingly endless. In this way, the essay has more in common with poetry than with the news stories we read in the paper. It elevates exploration above authority. It is an art form that celebrates the mysterious formulation of human thought.

The popularity of essays as a genre has skyrocketed in the past decade. In 2014, MacLean’s proclaimed essays to be the publishing trend of the year. More surprising still, many of the most popular collections or book-length essays coming out then were written by women. Eula Biss’s On Immunity, Lesley Jamison’s The Empathy Exams, Roxane Gay’s Bad Feminist. Even Helen Macdonald’s 2014 hit memoir H is for Hawk had a distinctly essayistic bent, weaving meditations on grief and loss with falconry, nature, and a shadow biography of the early 20th century queer novelist T. H. White. All of a sudden, it seemed, we wanted to know not just what women were doing, but what women thought.

Even creatives who were not strictly speaking “essayists” were encouraged in the trend. Comedian Amy Schumer was given a $1 million advance for an unwritten essay collection in 2012. She never wrote it, and cancelled the contract two years later, but then signed another contract with a different publisher in 2015 for close to $10 million. (That book, The Girl with the Lower Back Tattoo, came out in 2016 and was billed as biography, not essays, but was still a #1 New York Times bestseller.)

The essay as a genre has been on the rise since the beginning of the 21st century. As Phillip Lopate wrote for the Paris Review in 2021, as the new century dawned, essays were still considered “box office poison” in the publishing world. It was better to repackage your essays as a memoir. David Sedaris—a professional essayist more commonly referred to as a “humorist” or a comedian—became a household name after the publication of his 2000 runaway bestseller Me Talk Pretty One Day. It is as clear an example of an essay collection as you will find, but the cover did not say what kind of book it was. This was probably for the same reason that Sedaris did not and does not self-identify as an essayist, despite being one: this earlier negative connotation that essays were “box office poison.”

Then came the rise of the Internet with its blogs, forums, online magazines, and social media. For better and worse, we were all given a platform and a theoretical pathway to virality and fame. It was the century of the individual voice. The 2000s saw the meteoric ascendance of the personal essay, both as an art form and as harrowing, garish spectacle. Aspiring writers were encouraged to bare their souls to the readers of xoJane or Jezebel for $50 to $200 a pop. Bloggers were getting book deals, and those books were getting turned into movies, and so this seemed like a not unreasonable path to literary success. As Laura Bennett wrote in her now famous piece for Slate, “first-person writing has long been the Internet’s native voice.” The websites we logged onto every day—first out of curiosity, and then, increasingly, out of social and professional necessity, from the earliest iterations of Facebook to the current interface on Substack Notes—all asked us the same thing: What’s on your mind?

But then social media killed blogging and decimated the landscape of traditional print media. The tech industry and billionaire hangers-on enshittified social media. Now, award-winning professional authors and curious amateurs alike are being encouraged to resurrect the spectre of blogging and remake it as an entrepreneurial project. Enter the paid newsletter, the Substack. We’re being asked not just “what’s on your mind” but “how much can you get for it?”

Person after person, from Substack execs to self-styled newsletter gurus, have suggested that you might be able to get quite a lot, six figures even, to work from home in your pajamas. The appeal of that has proved almost irresistibly powerful, and for the most part, what’s for sale on Substack is simple: essays. Poems, and reviews, and recipes, and serialized fiction or memoir are here too, but it’s essays most of all. While it remains absurd to think of anything having to do with writing as a get-rich-quick scheme, essays—as a thing to read, as a thing to write, as a potential pathway to a lucrative full time income—are now more popular than ever before.

But what is an essay, and what makes it distinct from an article, an update, a column, or a blog post? Is there a distinction? How do you write an essay, and more importantly, how do you write a good one? How do you write one that is good enough to be published in a magazine or that you can charge subscribers for on Substack?

To write good, readable, professional-grade essays, it helps to understand the different essay forms; to study successful examples, understand the scope of what an essay can do, and learn how to do it.

Since August 2021 I have led a popular online essay-writing workshop called Essay Camp—if you’re a regular reader, you’ll know we just finished our latest session on Sunday—and I’ve learned a lot in the process. I’ve learned more about essays in my efforts to organize Essay Camp than I did in years of writing and publishing essays for the Paris Review, Granta, LitHub, Longreads, The Millions, The Rumpus, The Guardian, McSweeneys, or any of the other places that published me. Working with those editors helped me immensely to understand my own essays, in invaluable ways, but setting out to host Essay Camp these past few years has forced me to look at essay writing as a whole in a completely new way. I started writing in a new way myself, and realized that without even trying to, I’d written the first draft of a collection I can publish.

For a long time now I’ve been planning to write a series of essays about essays. I want to talk about the different essay forms that are popular now, or were popular in the past, and how to write them. I want to give examples, and explore the artistic, intellectual, and emotional effects and outcomes that those different forms can produce.

As I’ve said before during Essay Camp, there is not a universal, mutually agreed upon taxonomy of literary essay types. Common literary essay forms that you might have heard about include the “braided essay” or the “lyric essay,” but there is not a strong consensus on what precisely these two terms mean. There is also the “fragmented essay,” the “mimetic essay” or “hermit crab essay,” and the “vignette essay.” Outside of these forms, there are thematic types: the personal essay, the narrative essay, the topical essay, and the persuasive essay. There are very long essays and very short ones. There is the essayist as expert, the essayist as curator, the essayist as wonderer, the essayist as detective, and the essayist as unreliable narrator.

What is the difference between a longform article like you might read in The New Yorker, and an essay, which you might also read in The New Yorker? What are the differences between a personal essay or collection of personal essays, a diary, and a memoir? How does a vignette essay differ from flash nonfiction?

I’m going to be exploring all of these forms and types over the coming months in The Essay Series. I want to get to the heart of what essays are and what they do, and to compile a set of excellent examples for every type. Together, I’m hoping this will function as a powerful how-to guide for anyone hoping to write essays or to understand them.

The classification of essays into types will almost always be subjective to some extent. Unlike certain forms in poetry, like a villanelle, a haiku, or a sonnet, there are fewer hard and fast rules when it comes to what makes an essay belong to one category or another. Importantly, essays can be made up of different forms and different types.

You can think of the different essay forms, genres, and styles in this series as different colors on a palette. I can write about the color blue and how it differs from red, but that doesn’t mean you can’t or shouldn’t mix them up to make purple, violet, mauve, lilac, or any other shade you can think of.

If this is of interest to you, please be sure to subscribe below. These posts will be paywalled. Right now annual subscription fees are only $30 (€29), which is well below the Substack average, but that will change after November 30th. If you subscribe now, you can lock in that low rate.

If you’ve just completed Essay Camp and are wondering how to turn your rough draft freewrites into finished essays, this series is for you. If you already know how to write essays but just like nerding out on them and want to explore new forms, this series is for you too.

Thanks for reading!

Series Posts

The Essay Series #1: The Essay As Energy

The Essay Series # 2: The Vignette Essay

The Essay Series #3: The Essayist as Unreliable Narrator

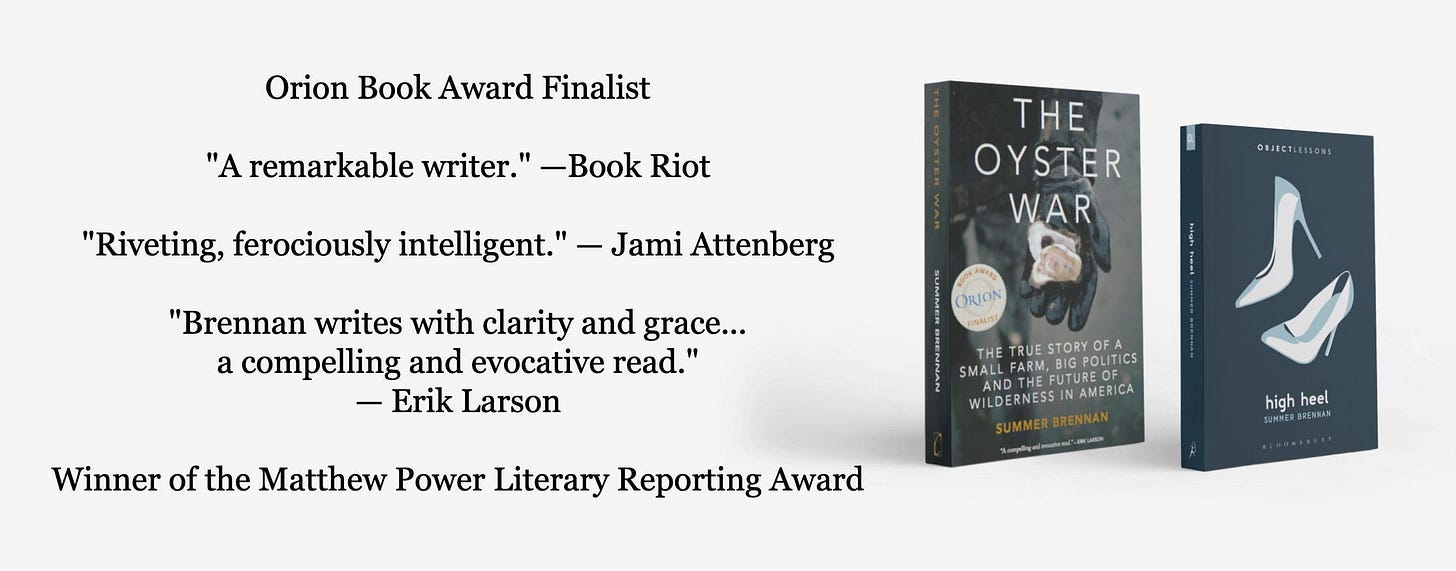

Enjoy my writing and want to support it? Become a paid subscriber today. You’ll get full access to craft talks, essays, notebook entries, sketchbook pages, and the popular semiannual write-along workshop Essay Camp. You can also buy my books The Oyster War and High Heel, “like” my posts by tapping the heart icon, share them on Substack Notes or other social media, and/or send them to a friend.

I have been thinking about this as well, how essays can be a form of personal storytelling. Thank you for sharing all this and for your class. It's been fun and inspiring to see all the different styles. And I love the word enshitify, ha! Good luck with your book!

This looks great, and I look forward to reading. Great essays can be life-changing. And on a less serious note, I'm thrilled that "enshittified" has now entered my lexicon!