The Labyrinth and Its Escape

Going Through Old Notebooks Part 19: On the Oulipo movement, the found rough draft, and writing with constraints.

A few years ago, Sheila Heti published a work of autofiction in the New York Times called A Diary in Alphabetical Order. Promoted as a “newsletter” (these were still the early days of the Substack boom) it was really a ten-part Oulipian serial, later published in book form.

As Heti herself explained:

“A little more than 10 years ago, I began looking back at the diaries I had kept over the previous decade. I wondered if I’d changed. So I loaded all 500,000 words of my journals into Excel to order the sentences alphabetically. Perhaps this would help me identify patterns and repetitions. How many times had I written, “I hate him,” for example? With the sentences untethered from narrative, I started to see the self in a new way: as something quite solid, anchored by shockingly few characteristic preoccupations. As I returned to the project over the years, it grew into something more novelistic. I blurred the characters and cut thousands of sentences, to introduce some rhythm and beauty. When The Times asked me for a work of fiction that could be serialized, I thought of these diaries: The self’s report on itself is surely a great fiction, and what is a more fundamental mode of serialization than the alphabet? After some editing, here is the result.”

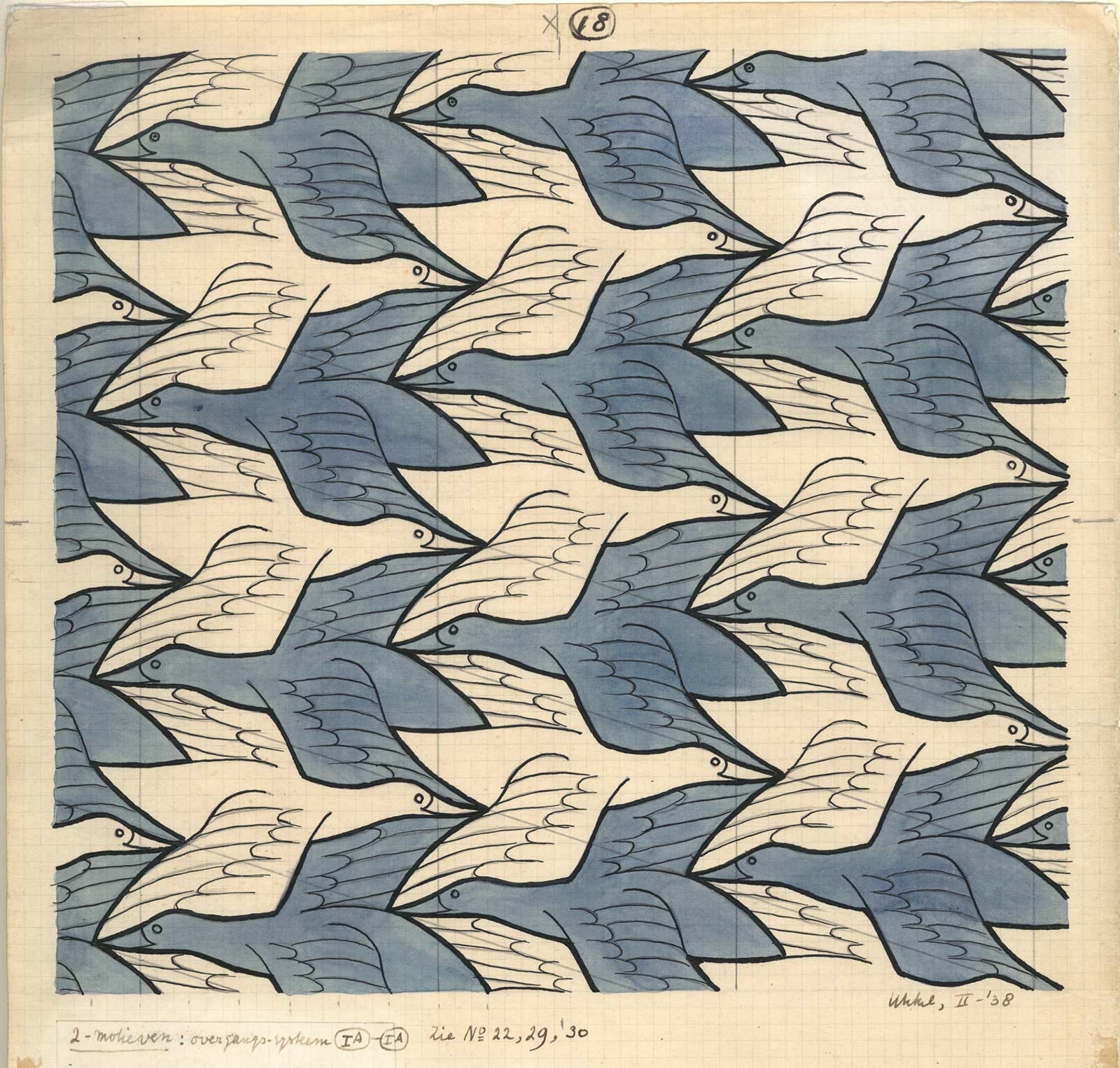

The novelist Raymond Queneau, who founded the Oulipo group of writers and mathematicians, along with chemical engineer François Le Lionnais, described his fellow Oulipians as “rats who construct the labyrinth from which they plan to escape.”

Oulipo stands for “Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle,” Ou-Li-Po, or the “workshop of potential literature.” In French, ouvroir also shares a root with the word “to open,” so they weren’t just workshopping these ideas, but opening the door to them. The word Oulipo also functions as an ambigram:

Well known works from the original Oulipo group include Queneau’s Exercises in Style, in which he describes the same altercation taking place on a bus in 99 different ways, and Georges Perec’s beloved An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris, a detailed account of three days spent sitting in cafés on the Place Saint-Sulpice. Another Oulipo member, Ambroise Perrin, prefigured Heti when he created a work called Madame Bovary dans l’ordre (“Madame Bovary in order”), in which every punctuation mark, number, and individual word of the novel is listed in alphabetical order. Julian Barnes described the end result like this:

“…By ‘list’, I mean list: the book has six vertical columns to a page, and prints out the word each time it occurs. So the word et, which features 2,812 times in the novel, is printed out 2,812 times, occupying almost nine full pages. La occurs 3,585 times, le 2,366 and les 2,276, elle 2,129 and lui a meagre 806 – from which you might perhaps deduce the sexual slant of the novel. Or not.”

There is something almost Zen about these works to me, in the exploration of repetition, in the invitation to consider the smallest moments as worthy of our deep attention. Queneau’s and Perec’s books—about a bus, about a city square—dare the reader to look and look and look at the same thing, the same place, the same minor event. They knock on the door of mundane reality until something else begins to open up. Something like transcendence. Even Perrin’s somewhat less poetic end product evokes the endearing innocence of a robot trying to understand a work of literature by taking it apart, tiny piece by tiny piece.

Oulipiana can manifest in many different ways. In what strikes me as a sort of Nouveau-Oulipian move, writer Joanna Walsh (who I must disclose is a friend), in one of the few truly creative uses of an LLM, used an AI bot to write five new 100,000-word books, after feeding it her entire oeuvre. Other recent works that flirt with Oulipian constraints or themes are Lauren Elkin’s 2021 memoir No. 91/92: A Diary of a Year on the Bus, and Heidi Julavits’s The Folded Clock, an out-of-order diary where each entry begins with the word “today.” Like Heti’s new series, both of these stem from the found rough draft of a diary.

I find a lot of these Oulipian works very tender. There’s something so touching, so oddly loving about giving this kind of gentle attention. There is also something very fertile to be found in them. The limitations that the writer places on the work can function as a sort of game, a literary version of “the floor is lava”—a structure within which ideas can grow. Setting rules for writing, a “constraint” as it’s commonly called, can be not so much a box as a trellis, a structure on which things can grow, revealing the transcendent nature of play. In this way, we plant the hedges of our labyrinth; in this way, we plot our escape.

This post is adapted from a notebook entry originally written in 2022.

You’ve just blasted through a whole new neural pathway in my brain… merci!!

Italo Calvino was a member and one of my favorite writers! His novel “If on a winter's night a traveler” seems perhaps influenced by this group, with its fractal and labyrinthian prose.