Words and Their Meaning

On titles, relationships, misunderstandings, slurs.

I want to talk about my daughter. Or one of them. I was going to have two daughters, one in 2021 and another in 2023. I saw them both on the sonogram monitor screens. They had passed all the usual early tests and time frames. Statistically, they should have been okay. They should have been safe, and seeing them there, these little curled beings floating in the darkness of space, in that secret dark ocean we all inhabit before life begins, they became real to me. Not just hypothetical, but actual, specific, individual, loved. Tiny cosmonauts, recognizably human, attached by a lifeline to their mothership, to me.

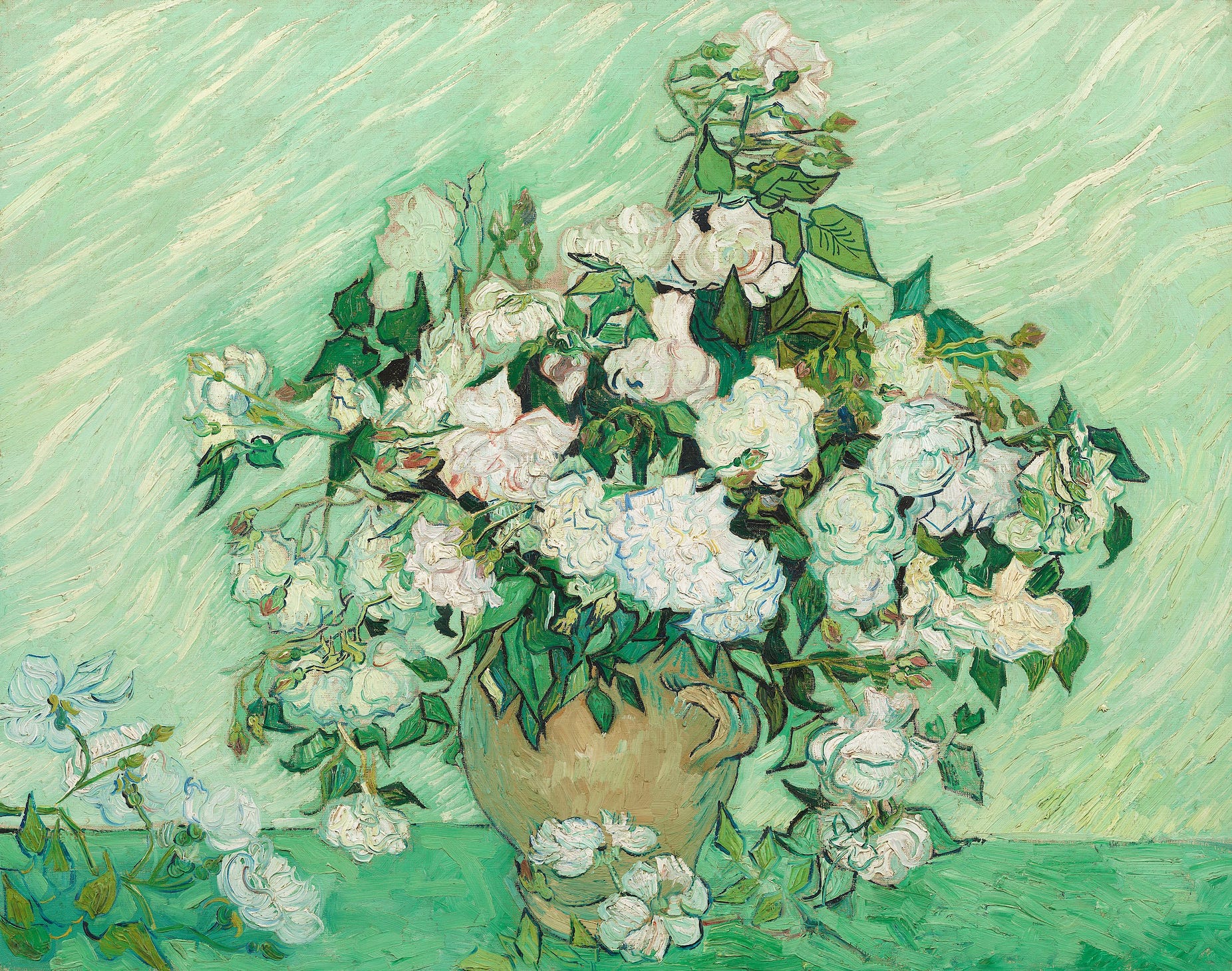

Nothing went wrong, exactly. The pregnancies were strong and healthy. But the human genome is complex, and we’re supposed to have a certain number of petals that make up the flowers that we are. No more, and no less. I have talked about this before. There are supposed to be forty-six petals on our flower, twenty three sets of two in all. Of course I’m talking about chromosomes, and when someone has an extra one, things can get complicated.

These extra petals are called “trisomies,” and having a trisomy can make your biological gender ambiguous, or it can make you shorter than you might have been otherwise, or it can make your muscles weaker, or your speech more difficult, or cause you to take a little longer to learn certain things or reach certain milestones. You might look a little different, or experience problems with some of your organs, or have a shortened lifespan.

Most of the time, that extra petal is dangerous. Fatal. The term I’ve seen is “embryonically lethal.” These additions, these variations implemented at random by the ever-inventive and experimental Mother Nature, at the time of conception, are not compatible with life. However, a few of these extra petals are compatible with life, or they are sometimes, and individuals with these trisomies can be born and live for anywhere from a few hours to many decades.

The best known of these is trisomy 21, usually called Down’s syndrome. This is the one most people have heard about, and if you’re going to have a trisomy, this is the one you want1. You’ll have some challenges, certainly, and your features will look a certain way that is identifiable to the casual observer, but otherwise you’re not really that different from anybody else.

Unfortunately, there is a lot of misinformation out there about this condition. You can still grow up, have hobbies, be an athlete, be an artist, go to college, get a job, have a romantic relationship, get married, love and be loved, and do most of the other things that people without this trisomy can do. Now that medical understanding of the condition has improved, your lifespan with Down’s syndrome has the potential to be the same as anyone else’s. Elizabeth Eastley, who was born with Down’s in 1945, just turned eighty years old this past November.2

Other trisomies are not so lucky. While a few are survivable, the prognosis is generally less favorable, with a higher incidence of “fetal demise,” and a considerably shorter lifespan when a full term birth is reached. Even Down’s syndrome is often lethal prior to birth, with up to 80 percent of all incidences ending in miscarriage at or before a mean gestational age of about 30 weeks3. But if things are working well enough with trisomy 21 for a baby to be born, most of the time, they’ll be more or less okay.

So, my daughter. The one I had wanted to talk about. She had one of these trisomies that is sometimes survivable, but in her case, was not. We didn’t do any genetic tests prior to her death, and only learned about her trisomy after the fact. She is buried in a cemetery in Paris, and this week I had to go to the mairie of the arrondissement where she was delivered, to request copies of her acte de décès, her death certificate, in which she is recorded as an enfant sans vie. It has been almost five years, and her plot in the cemetery must be renewed, and to do this her father and I must prove our succession rights.

I was already intimately familiar with this term—enfant sans vie, often shortened to ESV—from my work on 19th century artists, models, and courtesans. It occurs frequently in the historical ledgers of the civic archives of Paris. Many, many babies died in the 19th century before or during their own births. In this context, I was utterly normal: a foreign woman, living in Paris, who had lost a child. In English we use the term “stillborn.” In the United States, the certificates exist in their own category, but in France they are recorded along with everyone else.

On Friday, I walked from my apartment in the 2nd arrondissement to the mairie of another arrondissement, to obtain the necessary copies. It had been snowing at the start of the week, but now most of the snow was gone. The sky was gray, and a wind was picking up, which fluttered the red and gold ribbons tied to clusters of Christmas trees that still decorated intersections and squares of this festive city, soon to be dismantled.

I had not been inside this building since the day when we went to register her death. The office for civil records itself had been renovated since then, with new desks and partitions, but otherwise not much else had changed. There were more Christmas trees with red and gold ribbons in the lobby. I climbed the stairs to the correct office, took a number, and then went to wait on a reddish brown vinyl banquette.

Although I felt calm, or thought I did, it took me three tries to correctly fill out the records request form. My understanding of the different lines kept getting jumbled. I wrote down my daughter’s hyphenated last name, and then her first name, and then the names of her parents, and her legal dates of birth and death, which are the same. I circled one of the options provided to explain what qualified me to request this record, based on who I was in relation to the deceased: sa mère. Her mother.

It is only here, in this office, or at the cemetery, that I am someone’s mother. In all other settings, when asked if I am a mother, I am obliged to say no; to preserve the comfort level of the person or persons I am interacting with. When asked if I have children, I learned, after a few missteps, to just say no, with no caveats.

Here, it is different. My number is called, and I smile at the woman behind the desk and hand her my form, and when I say that I am here to request two copies of the acte de décès for ma fille, a stricken look passes briefly over her face. I hadn’t felt like crying at all before this, but in this moment, I suddenly fear I am about to. I look past the woman behind the desk to the patch of gray sky that is visible through the window beyond. There are the bare branches of a tree, and the outline of another building, the soft quiet of January. The feeling passes.

The woman across from me is French, and professional, and so she quickly dissolves the stricken look. She doesn’t say she’s sorry, or telegraph any pity, but we both know that for this brief moment, we are existing inside an unspoken bubble of grace. Her movements are careful. She swivels her chair, taps the keys. The acte is printed, stamped, notarized, and with the usual French pleasantries, I am on my way again in under ten minutes. These pieces of evidence that contain those secret words—daughter, mother— are tucked discreetly away in my purse.

A little over a week ago, right before the New Year, someone I know used the word retarded with me in a conversation. He was talking about politicians he didn’t like, and used this word as a slur to describe them.

“Please,” I said, “don’t use that word with me,”

“I’m using it on purpose,” he explained, oblivious in his political anger, and slightly tipsy on Scottish whiskey. “I want the language I use to match the severity of the situation.”

“Do not use that word with me,” I repeated, more strongly this time, or so I thought, but he didn’t get it, and didn’t stop or apologize, and I didn’t have the energy or inclination in that moment to explain.

Why should I have to? What is there to explain, anyway? That life is infinitely inventive? That some of us are a little different? That some of us keep living while others do not? That some of us get lots of time while others get none? That a word once used for the disabled should not be used as a slur to describe the evil, the incompetent, the detestable, the corrupt? That I am envious, always and forever envious, of the parents I see with living, disabled children, walking across squares or attending museums, trailing toys and coats. That grief is not always a dark room. That it can blow you open, push you out of yourself, force you into a state of unexplained grace. That this, too—yes, even this—can be a peaceful place; a landscape under a rain-washed sky; this earth that gives and then takes back again, covered in the reckless blossoms of weeds.4